A JOURNEY ThROUGH MULTITUDES: the sensory divination of srijon chowdhury's same old song

ESSAY REFLECTING ON srijon chowdhury’S SOLO EXHIBITION, SAME OLD SONG, AT The frye art museum, SEATTLE, may 2023

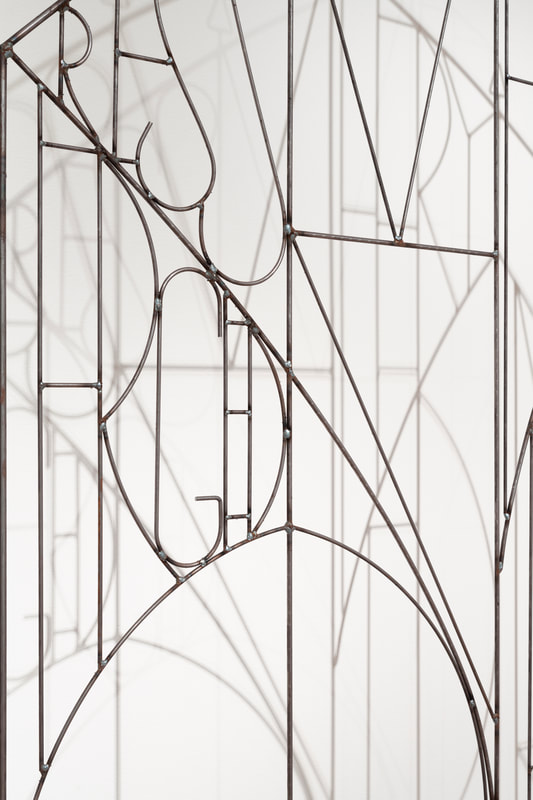

As I approach Srijon Chowdhury’s enigmatic Sigil Gate, I become aware of how it stands as an established marker; a delineation of the border between one space and another. A gate is meant to create an enclosure. But it can also act as a guide across unfamiliar borderlands.

In one way, the Sigil Gate embodies an aesthetic throughline of connectivity to the history of Mannerism, Symbolism, and the Munich Secession. Hanging low on the wall behind the gate is Die Sünde (Sin), a painting by one of the founders of the Munich Secession, Franz von Stuck. This green-pallored painting is just one version among many the artist created of his subject—a nude woman with dark cascading hair, cloaked beneath a large serpent draped across her shoulders. Her quiet, knowing gaze, fixed solidly upon us gazing back at her, is compelling and piercing. Why is she enclosed in this way? Is she an ancestor, a guide? A sentinel? A warning?

The Sigil Gate also signifies a journey from our waking, concrete world into a less absolutely defined one. This suggestion is reinforced by the presence of Die Sünde, but also by the somewhat Gothic architecture of the gate’s peaked arches, and threaded glyphs interlaced throughout its minimalist armature. The gate itself is a wrought-iron sculpture of words given form from William Blake’s poem, A Divine Image. Woven into the script is a protection spell authored by Srijon, the aesthetics of which remind me of the artistry of sigils found in 17th century grimoires.

Various words emerge and submerge as I read across its text. Terror. Secrecy. Forge. Certain shapes repeat themselves throughout, specifically the repeated shape of an eye—watchful, and as apotropaic as the iron that forms them. Not all who enter will receive the message of this poem, in which Blake describes humanity's potential to shape our world for better or worse, through descriptions of the human form. For those who do, they will carry the added layer of meaning with them, to reflect on later through the imagery in Srijon’s work. Bearing all this in mind, I step across the threshold and into the journey.

In one way, the Sigil Gate embodies an aesthetic throughline of connectivity to the history of Mannerism, Symbolism, and the Munich Secession. Hanging low on the wall behind the gate is Die Sünde (Sin), a painting by one of the founders of the Munich Secession, Franz von Stuck. This green-pallored painting is just one version among many the artist created of his subject—a nude woman with dark cascading hair, cloaked beneath a large serpent draped across her shoulders. Her quiet, knowing gaze, fixed solidly upon us gazing back at her, is compelling and piercing. Why is she enclosed in this way? Is she an ancestor, a guide? A sentinel? A warning?

The Sigil Gate also signifies a journey from our waking, concrete world into a less absolutely defined one. This suggestion is reinforced by the presence of Die Sünde, but also by the somewhat Gothic architecture of the gate’s peaked arches, and threaded glyphs interlaced throughout its minimalist armature. The gate itself is a wrought-iron sculpture of words given form from William Blake’s poem, A Divine Image. Woven into the script is a protection spell authored by Srijon, the aesthetics of which remind me of the artistry of sigils found in 17th century grimoires.

Various words emerge and submerge as I read across its text. Terror. Secrecy. Forge. Certain shapes repeat themselves throughout, specifically the repeated shape of an eye—watchful, and as apotropaic as the iron that forms them. Not all who enter will receive the message of this poem, in which Blake describes humanity's potential to shape our world for better or worse, through descriptions of the human form. For those who do, they will carry the added layer of meaning with them, to reflect on later through the imagery in Srijon’s work. Bearing all this in mind, I step across the threshold and into the journey.

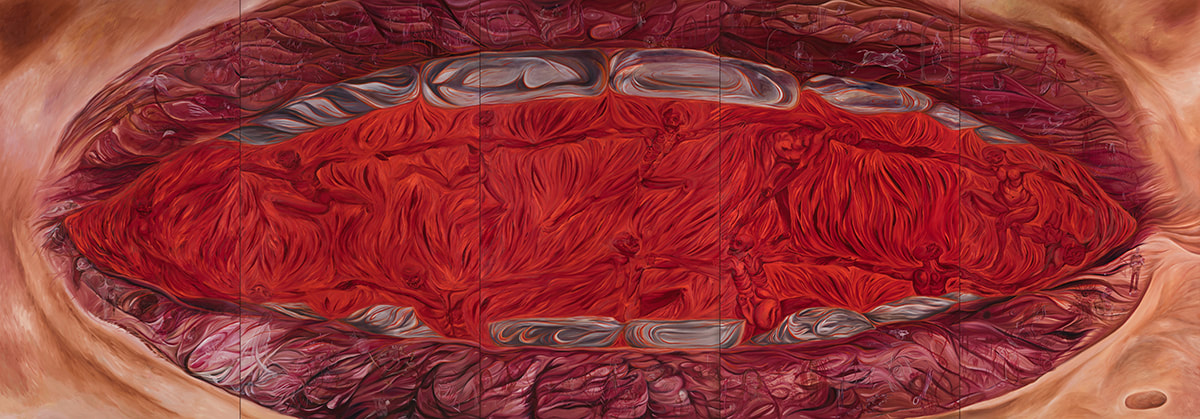

As I pass through, I enter into the vast emptiness of the main gallery which has become a cathedral to painting; an expansive silent space made sacred. Open fields of bare walls around each painting make monuments of the work, but also create a sense of intimacy. Somehow, even as they appear larger than life, they scale down to feel almost mortal; to suggest a connectivity between the physicality of our respective bodies, standing together. The paintings themselves are enlarged closeups of facial features in almost overbearing texture and detail. Through these, we are then able to see layers of self-portraiture. Occasionally, contained within each facial feature are several smaller scenes which sometimes reference Srijon’s life, or past works. Some of these renderings are harsh and visceral, conveying both beauty and abjection, attraction and horror. As such, they seem to translate the primordial fear and anxiety of danger and death in the Sublime landscape to the terrain of the flesh. The dominant color throughout each of these is a brilliant crimson—the universal color of blood, ancestors, intergenerational connectivity, and life force. Red is a root, and a tether across time.

The way Srijon’s paintings focus primarily on the sensory organs of eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, feels deeply significant. They illustrate how our perceptions of self, reality, and spirituality are translated through all that we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. Throughout each moment across a lifetime the self perceives and receives, integrates and incorporates, masticates and regurgitates; simultaneously creating and destroying our multitudes of reality. Our material and ideological interpretation makes our stories about the past and future, dreams and memories, and imaginal realms even more potent and meaningful. Reflecting on the layered experience of subjective existence, and the overlaps in our collective understanding of love, fear, death, and life; I begin a slow circle around the gallery to examine each of Srijon’s paintings, and features.

The eyes show us their depths, but also reflections. Portrayed in the iris of Eye (Morning Glory) is a hand holding a bright red morning glory blossom. Also known as bindweed, its seeds are known to have hallucinogenic properties. Humans have used plants like this since time immemorial to assist their journeys to different realms, from waking life to dream life, from mundane worlds to spiritual ones. These are ritualized methods of acquiring wisdom, and they may even strengthen the tether between corporeal life and spirit. Below the morning glory is another hand holding a knife. Its blade, reflecting the crimson flower it has presumably just cut, gives the illusion of dripping blood. The knife appears to represent a choice, and in choosing, severs the connection between this world and the other. Reflected in the iris of Eye (Birth) is a water birth, a journey from some unknown place to this one; a shift from what we ordinarily consider in regards to these passages. From where do we come, and which way are we going? Do we choose this life? Birth is equally as profound and mysterious an entry into the world as death's exit from it. We are born in blood, and when the umbilical cord is cut it severs the tangible connection between mother and child, child and otherworld. It seems even the transportation between realities, like reality itself, is relative and illusory.

Nose (Crucifixion) shows Christ in the posture of the cross, painted as an elongated El Greco-like figure with his hands clawing in a contorted rigor. His head is bowed, a crown of thorns prominently encircling his head like a radiant red sun. His body is bathed in bright red, suggesting the affliction of his wounds, and the offering of his sacrifice. To have this figure overlaid across the nose strikes me as a kind of shield, like that from an ancient style of helmet, to ward and protect. What are we willing to relinquish to find salvation, fulfillment, and new life? What, and whom, do we protect?

In Ear (Good), a winged angel emerges to pull a red cord of entrails from the tormented screaming figure who follows. In the other, Ear (Bad), a Goya-esque demon pierced with blades devours one poor soul with another in hand, while yet another protrudes from their bloodied head. Each of these images have deeper implications, alluding to the influence of our multifaceted natures, but also to the influence of a kind of spell. The ears are receptive portals to whisperings and influences we may go on to enact ourselves; good and evil, angel and devil, benefic and malefic, or foolish and wise. What shapes do these influences take in our world through our actions? Do we succumb to, or overcome, our deepest fears and subconscious nightmares?

What the eyes, nose, and ears interpret, the mouth consumes, and brings forth. What goes in, inevitably comes out; the stories we hear, and the stories we tell. Mouth (Divine Dance) is the most explicit of all Srijon’s imageries, a descendent of the medieval Hellmouth. Within it are all manner of manifestations—ghosts and memories, fire and flayed figures, divine spirits and demons, plants and animals, future ghosts and ancestors. The teeth appear metallic and liquid and the tongue is a menace, indistinguishable from the throat; a boiling pit of molten rock and brimstone. The mouth brings to bear all that lies within us. What is spoken, lives; expelled to levy curses upon our foes, or blessings upon those most beloved. While the hell of the self is real for us all, this is not an inescapable descent into madness or torment. Srijon isn’t proselytizing on sin or virtue. Instead, he’s speaking to the power of memory, of all that has made us who we've been, and who we will become.

The way Srijon’s paintings focus primarily on the sensory organs of eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, feels deeply significant. They illustrate how our perceptions of self, reality, and spirituality are translated through all that we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. Throughout each moment across a lifetime the self perceives and receives, integrates and incorporates, masticates and regurgitates; simultaneously creating and destroying our multitudes of reality. Our material and ideological interpretation makes our stories about the past and future, dreams and memories, and imaginal realms even more potent and meaningful. Reflecting on the layered experience of subjective existence, and the overlaps in our collective understanding of love, fear, death, and life; I begin a slow circle around the gallery to examine each of Srijon’s paintings, and features.

The eyes show us their depths, but also reflections. Portrayed in the iris of Eye (Morning Glory) is a hand holding a bright red morning glory blossom. Also known as bindweed, its seeds are known to have hallucinogenic properties. Humans have used plants like this since time immemorial to assist their journeys to different realms, from waking life to dream life, from mundane worlds to spiritual ones. These are ritualized methods of acquiring wisdom, and they may even strengthen the tether between corporeal life and spirit. Below the morning glory is another hand holding a knife. Its blade, reflecting the crimson flower it has presumably just cut, gives the illusion of dripping blood. The knife appears to represent a choice, and in choosing, severs the connection between this world and the other. Reflected in the iris of Eye (Birth) is a water birth, a journey from some unknown place to this one; a shift from what we ordinarily consider in regards to these passages. From where do we come, and which way are we going? Do we choose this life? Birth is equally as profound and mysterious an entry into the world as death's exit from it. We are born in blood, and when the umbilical cord is cut it severs the tangible connection between mother and child, child and otherworld. It seems even the transportation between realities, like reality itself, is relative and illusory.

Nose (Crucifixion) shows Christ in the posture of the cross, painted as an elongated El Greco-like figure with his hands clawing in a contorted rigor. His head is bowed, a crown of thorns prominently encircling his head like a radiant red sun. His body is bathed in bright red, suggesting the affliction of his wounds, and the offering of his sacrifice. To have this figure overlaid across the nose strikes me as a kind of shield, like that from an ancient style of helmet, to ward and protect. What are we willing to relinquish to find salvation, fulfillment, and new life? What, and whom, do we protect?

In Ear (Good), a winged angel emerges to pull a red cord of entrails from the tormented screaming figure who follows. In the other, Ear (Bad), a Goya-esque demon pierced with blades devours one poor soul with another in hand, while yet another protrudes from their bloodied head. Each of these images have deeper implications, alluding to the influence of our multifaceted natures, but also to the influence of a kind of spell. The ears are receptive portals to whisperings and influences we may go on to enact ourselves; good and evil, angel and devil, benefic and malefic, or foolish and wise. What shapes do these influences take in our world through our actions? Do we succumb to, or overcome, our deepest fears and subconscious nightmares?

What the eyes, nose, and ears interpret, the mouth consumes, and brings forth. What goes in, inevitably comes out; the stories we hear, and the stories we tell. Mouth (Divine Dance) is the most explicit of all Srijon’s imageries, a descendent of the medieval Hellmouth. Within it are all manner of manifestations—ghosts and memories, fire and flayed figures, divine spirits and demons, plants and animals, future ghosts and ancestors. The teeth appear metallic and liquid and the tongue is a menace, indistinguishable from the throat; a boiling pit of molten rock and brimstone. The mouth brings to bear all that lies within us. What is spoken, lives; expelled to levy curses upon our foes, or blessings upon those most beloved. While the hell of the self is real for us all, this is not an inescapable descent into madness or torment. Srijon isn’t proselytizing on sin or virtue. Instead, he’s speaking to the power of memory, of all that has made us who we've been, and who we will become.

Srijon uses allegory and metaphor to excavate the layers of both undesirable and desirable pieces of our humanity through the process of story. His symbols are personal to him, and universal to us, illustrating great ordeals as moments of profound change, and cycles of birth and death. They're sometimes quiet or tender, sometimes catastrophically life-changing and chaotic, reminding us that all disruption leads to growth. The narrative, built from his own past work and life experience, establishes itself within the mind, and the climactic story takes place at the site of narration, the mouth, to speak of opportunity through what appears to be the eruption of apocalypse. But rather than signifying an end in itself, a terminus, this becomes an event signaling the collapse of illusory veils, of that which we had previously believed or held dear, to embark upon the deep excavation of revelation and rebirth.

Such a shift in perspective allows us to reframe a reality in which former patterns, behaviors, ways of thinking or being and moving are interrupted. Old ideas or stories about ourselves and the world that could not otherwise be released, deceptions, and other misguided notions, are set free. An apocalypse presents us with a beginning in which we are liberated from the past but grounded enough to build on a foundation rooted firmly in memory. If honoring our before shapes how we are to be after, then we know that our origins don’t spring up from a single point in time, or from nothing—many former, valuable pieces remain that can be completely reimagined. We're always building the future from the past, there is no true tabula rasa. Our renewal, combining former parts of us to evolve into whatever comes next, is an alchemy of transformation, creating new material from a diverse array of elements that transcend their base parts; none of which could result in the same outcome on their own but culminate together in our new form. What we do with the pieces that remain determines where and how we go. As Blake suggests in his poem, it is through our renewal that we begin to forge a new path.

I find myself slowly returning to the world of my own senses, and I step back to reexamine the relationship of my body to these paintings. Their intimacy and impact lingers in the wake of our conversation. And so as I turn to walk once again through the Sigil Gate, departing from liminal space into concrete reality, I’m aware of how deeply Srijon’s work has guided me through its dreamlike storytelling; and how thoroughly reflective his sensory divination has left me. Just as Franz von Stuck painted multiple versions of Die Sünde, Srijon has also recreated multiple versions of his work and himself, which mirrors our own multitudes back to us. Who have we been in this world, now; who are we now, in future worlds? Srijon’s portrayal of humanity, history, purpose, and place through his senses and memories, incantations and poetry, illustrates how these questions are complicated for us all. As we live and move through the world, each disruption whether large or small, trial or triumph, is an initiation into a new way of being that instigates further metamorphosis. We are all constantly shapeshifting. Srijon depicts figures in the midst of such change, from past to present, from memory to reality, from alone to among family, from earthly realms to heavenly or hellish ones. He is showing us how we are all things at once; beginnings and endings, living and dying, existing within a continuous flow of all our dreams, nightmares, realities, and possibilities.

The dark-haired harbinger of these revelations, Die Sünde (Sin), smiles at me as I walk past as if to say, Do you now see our multitudes? And I say, Yes, I surely do. We have journeyed alongside and through many gates to arrive here in this space between many things. The world has transformed, and we with it.

Such a shift in perspective allows us to reframe a reality in which former patterns, behaviors, ways of thinking or being and moving are interrupted. Old ideas or stories about ourselves and the world that could not otherwise be released, deceptions, and other misguided notions, are set free. An apocalypse presents us with a beginning in which we are liberated from the past but grounded enough to build on a foundation rooted firmly in memory. If honoring our before shapes how we are to be after, then we know that our origins don’t spring up from a single point in time, or from nothing—many former, valuable pieces remain that can be completely reimagined. We're always building the future from the past, there is no true tabula rasa. Our renewal, combining former parts of us to evolve into whatever comes next, is an alchemy of transformation, creating new material from a diverse array of elements that transcend their base parts; none of which could result in the same outcome on their own but culminate together in our new form. What we do with the pieces that remain determines where and how we go. As Blake suggests in his poem, it is through our renewal that we begin to forge a new path.

I find myself slowly returning to the world of my own senses, and I step back to reexamine the relationship of my body to these paintings. Their intimacy and impact lingers in the wake of our conversation. And so as I turn to walk once again through the Sigil Gate, departing from liminal space into concrete reality, I’m aware of how deeply Srijon’s work has guided me through its dreamlike storytelling; and how thoroughly reflective his sensory divination has left me. Just as Franz von Stuck painted multiple versions of Die Sünde, Srijon has also recreated multiple versions of his work and himself, which mirrors our own multitudes back to us. Who have we been in this world, now; who are we now, in future worlds? Srijon’s portrayal of humanity, history, purpose, and place through his senses and memories, incantations and poetry, illustrates how these questions are complicated for us all. As we live and move through the world, each disruption whether large or small, trial or triumph, is an initiation into a new way of being that instigates further metamorphosis. We are all constantly shapeshifting. Srijon depicts figures in the midst of such change, from past to present, from memory to reality, from alone to among family, from earthly realms to heavenly or hellish ones. He is showing us how we are all things at once; beginnings and endings, living and dying, existing within a continuous flow of all our dreams, nightmares, realities, and possibilities.

The dark-haired harbinger of these revelations, Die Sünde (Sin), smiles at me as I walk past as if to say, Do you now see our multitudes? And I say, Yes, I surely do. We have journeyed alongside and through many gates to arrive here in this space between many things. The world has transformed, and we with it.

This essay was originally printed in a self-published catalog by Srijon Chowdhury, created to include alongside his work at Independent New York in May 2023. Make sure to check out more of Srijon's work at the links below.

Srijon Chowdhury

Foxy Production

Frye Art Museum

Srijon Chowdhury

Foxy Production

Frye Art Museum