THIS IS FOR LOVE LETTERS

Catalog essay for Joey Veltkamp’s exhibition at ArtsWest, Seattle, This Is Not A Protest, It’s A Celebration!

Sharon Arnold

Joey Veltkamp is unfolding one of the largest quilts I’ve seen him make, meant to envelop not just one body but two. The largest patches are made from a friend’s red plaid lumberjack flannel; one pocket prominently, lovingly, placed near the top of the blanket. “... this is for love letters,” Joey explains as he pats the pocket and flattens out the quilt. I nearly die from the sweetness, the sincerity of the remark, and absolute romance of the thought that a quilt could be made to contain such a thing.

It fits to hear those words come from Joey’s lips. After all, his entire body of work is a love letter. Even when the work is about mundane objects, Veltkamp is reaching out from deep within his heart to express something tangible about the emotions we’re feeling. In the truest sense, he is drawing from a long history of art made from love and nurture, creating objects with beauty and meaning, embodying the stories and memories of people and communities.

In 1987, a group of close friends wished to honor the multitude of deaths that AIDS had wreaked upon the gay community. Their response was to create a quilt memorializing the names of people who had died. Their effort became known as The AIDS Memorial Quilt, founded by The NAMES Project Foundation. Born out of anguish, the NAMES Project has served as a monument to the catastrophic effect the virus had not only on individual lives, but entire communities, and a culture. This project points at those lives and humanizes them. These were people, not numbers or statistics. The immediate personal impact of this illness was devastating, and through the act of sewing – a form of mending - and naming, the AIDS Memorial Quilt became an act of healing.

The spectre of the Memorial Quilt is real. Its purpose was to commemorate the ghosts of people we remember and heal those who remain. In 2011, Joey Veltkamp exhibited a collection of colorful, pinched clay ghost sculptures at SOIL Gallery in Seattle to document his own journey through sadness. Sweet, simple, and playful, they were small protagonists in a story about grief without a name or a place. They served as symbols of people – friends, old celebrities, fictional characters – but over time they became friendly, warm, and comforting fixtures. It is from these that a new body of work emerged, a series of drawings Veltkamp made based on the shape, color, and repetition of form inspired by piles of blankets. Like ghosts, blankets are imbued with the presence of a person. Unlike ghosts, they don’t hold the shape of the person beneath them. Still, they are altered by our interaction, carrying our scent when we’re gone. Blankets and quilts hold us when others can’t. They keep us warm. Soft, cozy, and sometimes fluffy; they are in the truest sense of the word, “comforters”.

It fits to hear those words come from Joey’s lips. After all, his entire body of work is a love letter. Even when the work is about mundane objects, Veltkamp is reaching out from deep within his heart to express something tangible about the emotions we’re feeling. In the truest sense, he is drawing from a long history of art made from love and nurture, creating objects with beauty and meaning, embodying the stories and memories of people and communities.

In 1987, a group of close friends wished to honor the multitude of deaths that AIDS had wreaked upon the gay community. Their response was to create a quilt memorializing the names of people who had died. Their effort became known as The AIDS Memorial Quilt, founded by The NAMES Project Foundation. Born out of anguish, the NAMES Project has served as a monument to the catastrophic effect the virus had not only on individual lives, but entire communities, and a culture. This project points at those lives and humanizes them. These were people, not numbers or statistics. The immediate personal impact of this illness was devastating, and through the act of sewing – a form of mending - and naming, the AIDS Memorial Quilt became an act of healing.

The spectre of the Memorial Quilt is real. Its purpose was to commemorate the ghosts of people we remember and heal those who remain. In 2011, Joey Veltkamp exhibited a collection of colorful, pinched clay ghost sculptures at SOIL Gallery in Seattle to document his own journey through sadness. Sweet, simple, and playful, they were small protagonists in a story about grief without a name or a place. They served as symbols of people – friends, old celebrities, fictional characters – but over time they became friendly, warm, and comforting fixtures. It is from these that a new body of work emerged, a series of drawings Veltkamp made based on the shape, color, and repetition of form inspired by piles of blankets. Like ghosts, blankets are imbued with the presence of a person. Unlike ghosts, they don’t hold the shape of the person beneath them. Still, they are altered by our interaction, carrying our scent when we’re gone. Blankets and quilts hold us when others can’t. They keep us warm. Soft, cozy, and sometimes fluffy; they are in the truest sense of the word, “comforters”.

It would be easy to assume that a craft-based practice imposes "less" pressure on an artist. After all, quilts don’t carry the burden of Eurocentric notions of art history. But they do carry an honest history of art and artmaking; as well as the extensive history of craft-making, nurture, caretaking, and the art of people across cultures and across time. Perhaps the most famous among them are the stunning, colorful, and boldly abstract quilts made by the Women of Gee’s Bend. The work of these Black women from Alabama can now be seen across modern art museums and galleries all over the US, something I’m certain those making them never imagined would happen. And why would they? These quilts were not made for that purpose in mind. Outside the confines of the capitalist "art world", textile arts are passed on through generations of people, and made intimately in small gatherings. They are a language of culture, storytelling, and identity. Not made for the distanced perspective of a sterile exhibition, they are an intimate document and history of a people, for the people. Quilts are a recording of moments in time, a memory of ancestors, and a living breathing memory for descendants. They are a portrait of both the person who made them, and the person for whom they are made. But the people making them have historically remained invisible.

I am reminded of an essay by Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mother's Gardens, in which she describes the way Black women never stopped creating artworks, or pouring themselves into creativity. Quilt-making has long been relegated to the work of women confined to the home, who were expected to take care of their men and children; often at the sacrifice of self and desire. Historically, while men’s work is expressly tied to the notion of identity and recognition, women have labored without any expectation of it. In these traditional heteronormative roles, defined by white supremacy, men are celebrated for their work, and women are only noticed when the work expected of them isn’t done. And yet women do dream, and have stories to tell. While it would be dangerously problematic to exotify the struggles of Black women creators, it's worth noting with respect that those who are driven to create will do so irrespective of and in spite of oppression, to use what is at hand, and to defy total death of the voice and the self through the act of creation. Walker brings these women forward by naming them "our mothers and grandmothers", implying an unbroken legacy to be carried forward into perpetuity. Like Walker's women, the Women of Gees Bend are also mothers and grandmothers, sisters, aunts, and daughters who stand tall across multiple histories of making, and storytelling, never to be forgotten.

The interconnectivity of queer relationships and histories also threads and weaves itself across communities and across time. Literature, art, craft, and music made by queer creators reminds us of our ongoing histories of place, identity, creativity, hardship, and activism. These movements are led by BIPOC leaders who must continually shift and move to stay ahead of appropriation, subjugation, and oppression. Like Alice Walker's women, their creative legacies defy the insistence of society to erase them. Throughout it all is a rich tapestry of stories told by ancestors who survived, endured, and died; and by those living creators who are here to carry our stories forward through time, never to be forgotten.

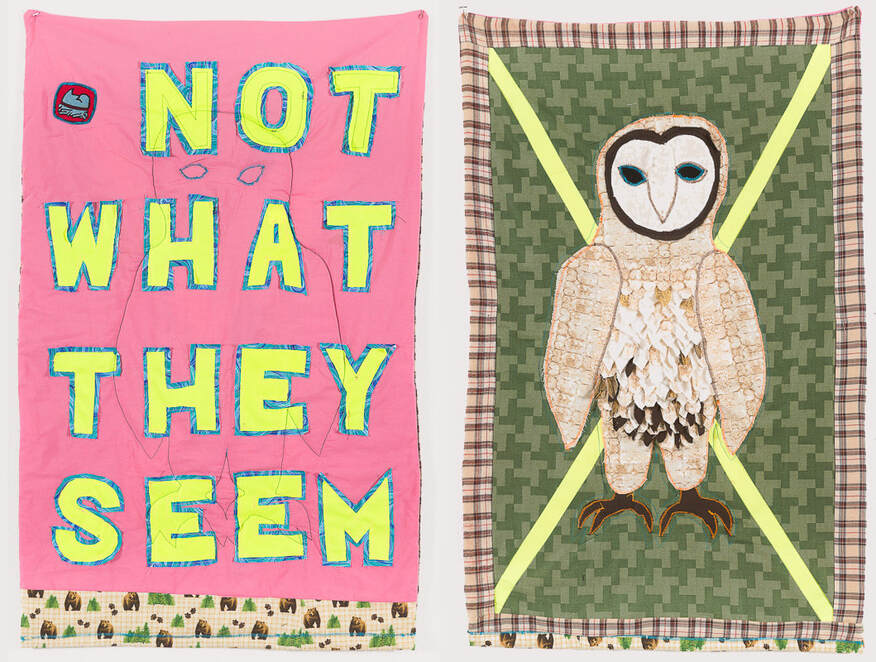

Carrying this tradition, Joey Veltkamp is creating a series of quilts and flags where color forms stories of identity through symbolism. Common themes of alienation or weirdness emerge, for example, in the way he uses neon, giving us a visual clue that there is something happening or about to happen. This use of color is a marker of uncanny Pacific Northwest energy, a sign of something strange or supernatural. Veltkamp loves to touch on the persistent mythology of this rainy, dark, and mystical region - our penchant for vampires, Otherworldly creatures, and long dark winters creates a sort of Nordic feeling of weirdness, the in-between, and the supernatural. The Northwest, a historically restless location in the furthermost corner of the lower 48 States, is a home to those who didn't quite fit in anywhere else; mystics, weirdos, and outcasts.

Veltkamp often points to these cultural references or people in his flags. Through them, he celebrates feminist, queer, pop, and subcultural remembrances or slogans. One quilt evokes a historical banner declaring, A Day Without Lesbians Is Like A Day Without Sunshine, or a wise PNW idiom that sagely warns The Owls Are Not What They Seem. He pulls an uncanny quote from a Nirvana song, No Recess, evoking the scratchy voice of Kurt Cobain who notoriously spraypainted God is Gay on his pickup truck in Aberdeen. Or they cite a ballad of strength such Alicia Keys’ That Girl is On Fire. Each of these embody a duality which reflects the history of the music they reference. Like old 45s, the flags have “A sides” and “B sides”, often containing two different texts or an image and a text that correspond with one another.

I am reminded of an essay by Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mother's Gardens, in which she describes the way Black women never stopped creating artworks, or pouring themselves into creativity. Quilt-making has long been relegated to the work of women confined to the home, who were expected to take care of their men and children; often at the sacrifice of self and desire. Historically, while men’s work is expressly tied to the notion of identity and recognition, women have labored without any expectation of it. In these traditional heteronormative roles, defined by white supremacy, men are celebrated for their work, and women are only noticed when the work expected of them isn’t done. And yet women do dream, and have stories to tell. While it would be dangerously problematic to exotify the struggles of Black women creators, it's worth noting with respect that those who are driven to create will do so irrespective of and in spite of oppression, to use what is at hand, and to defy total death of the voice and the self through the act of creation. Walker brings these women forward by naming them "our mothers and grandmothers", implying an unbroken legacy to be carried forward into perpetuity. Like Walker's women, the Women of Gees Bend are also mothers and grandmothers, sisters, aunts, and daughters who stand tall across multiple histories of making, and storytelling, never to be forgotten.

The interconnectivity of queer relationships and histories also threads and weaves itself across communities and across time. Literature, art, craft, and music made by queer creators reminds us of our ongoing histories of place, identity, creativity, hardship, and activism. These movements are led by BIPOC leaders who must continually shift and move to stay ahead of appropriation, subjugation, and oppression. Like Alice Walker's women, their creative legacies defy the insistence of society to erase them. Throughout it all is a rich tapestry of stories told by ancestors who survived, endured, and died; and by those living creators who are here to carry our stories forward through time, never to be forgotten.

Carrying this tradition, Joey Veltkamp is creating a series of quilts and flags where color forms stories of identity through symbolism. Common themes of alienation or weirdness emerge, for example, in the way he uses neon, giving us a visual clue that there is something happening or about to happen. This use of color is a marker of uncanny Pacific Northwest energy, a sign of something strange or supernatural. Veltkamp loves to touch on the persistent mythology of this rainy, dark, and mystical region - our penchant for vampires, Otherworldly creatures, and long dark winters creates a sort of Nordic feeling of weirdness, the in-between, and the supernatural. The Northwest, a historically restless location in the furthermost corner of the lower 48 States, is a home to those who didn't quite fit in anywhere else; mystics, weirdos, and outcasts.

Veltkamp often points to these cultural references or people in his flags. Through them, he celebrates feminist, queer, pop, and subcultural remembrances or slogans. One quilt evokes a historical banner declaring, A Day Without Lesbians Is Like A Day Without Sunshine, or a wise PNW idiom that sagely warns The Owls Are Not What They Seem. He pulls an uncanny quote from a Nirvana song, No Recess, evoking the scratchy voice of Kurt Cobain who notoriously spraypainted God is Gay on his pickup truck in Aberdeen. Or they cite a ballad of strength such Alicia Keys’ That Girl is On Fire. Each of these embody a duality which reflects the history of the music they reference. Like old 45s, the flags have “A sides” and “B sides”, often containing two different texts or an image and a text that correspond with one another.

The flags feel celebratory but they are also a call to attention. They are evocative of banners carried by activists during a march, containing short but memorable words to carry home and not forget. But rather than protest, they serve as an homage to the heroes in his life, people who are in his words folks who create space. And in fact, while Veltkamp neither self-identifies nor is designated as an activist artist, he has a history of engaging activism in his artistic practice by declaring and creating space. Whether that’s been through his blog Best Of, using his studio residency at Seattle University for a series of workshops taught by artists in the Seattle community, or creating the Seattle Women’s Convention at the Hedreen Gallery (again, at Seattle University); this is precisely what Joey’s activism looks like. He clears the stage for others to speak, or just be.

Veltkamp’s work could be read as pop art, not only because of its cultural references but because of its colorful iconography which references a media-rich world. But playing with both subject matter and object-ness, Veltkamp’s works describes an art historical lineage that traces itself back to the work of Jasper Johns - a gay artist whose lover was Robert Rauschenberg - who treated the duality of his works with a distinct philosophy that they could be all things at once, both subject and object, formal composition and material. He defied the macho-ism of his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, whose work was more like a stamp of their personality, and instead pursued conveying symbols outside of their assigned meaning or value. Johns’ best examples of painting as object, separate from symbol, are his series of flag paintings or targets. Both toyed with our attachment to the symbol's designation while declaring their presence as formal constructions. The game is in our attention to the sign, as well as its life as an independent work of art. Johns once said:

Sometimes I see it and then paint it. Other times I paint it and then see it. Both are impure situations, and I prefer neither. At every point in nature there is something to see. My work contains similar possibilities for the changing focus of the eye.

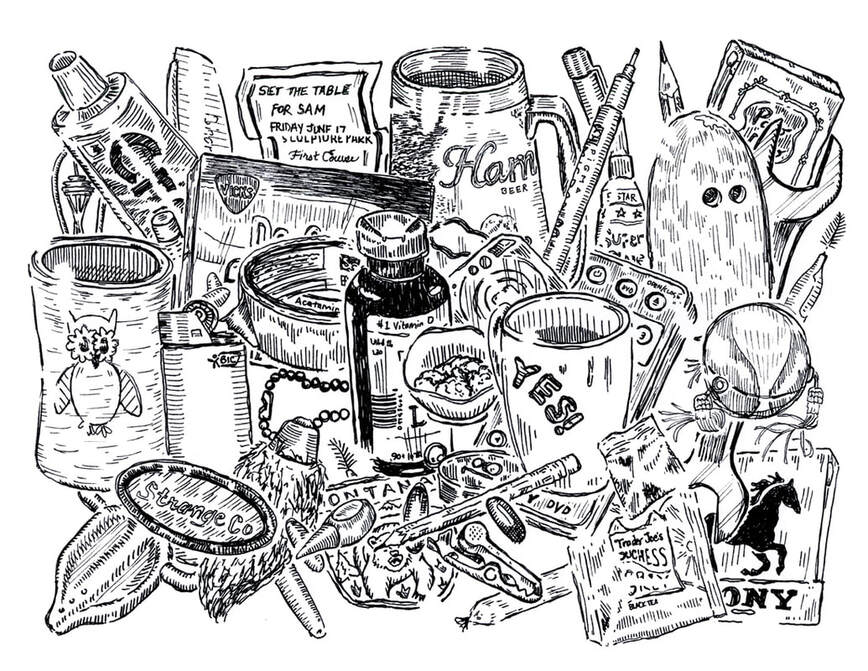

This points back to Veltkamp’s still lifes (the diary drawings) and his blanket series, which are collections of things demanding to be viewed out of context as a collection of marks on paper. He draws them because he sees them; he sees them, therefore he draws them.

Veltkamp’s work could be read as pop art, not only because of its cultural references but because of its colorful iconography which references a media-rich world. But playing with both subject matter and object-ness, Veltkamp’s works describes an art historical lineage that traces itself back to the work of Jasper Johns - a gay artist whose lover was Robert Rauschenberg - who treated the duality of his works with a distinct philosophy that they could be all things at once, both subject and object, formal composition and material. He defied the macho-ism of his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, whose work was more like a stamp of their personality, and instead pursued conveying symbols outside of their assigned meaning or value. Johns’ best examples of painting as object, separate from symbol, are his series of flag paintings or targets. Both toyed with our attachment to the symbol's designation while declaring their presence as formal constructions. The game is in our attention to the sign, as well as its life as an independent work of art. Johns once said:

Sometimes I see it and then paint it. Other times I paint it and then see it. Both are impure situations, and I prefer neither. At every point in nature there is something to see. My work contains similar possibilities for the changing focus of the eye.

This points back to Veltkamp’s still lifes (the diary drawings) and his blanket series, which are collections of things demanding to be viewed out of context as a collection of marks on paper. He draws them because he sees them; he sees them, therefore he draws them.

The transition from soft quilts into draughtsmanship formalizes them. They recall Veltkamp’s diary drawings which described his life and the lives of those he knew, giving weight and meaning to mundanity, a pile we might not otherwise give attention to. He has given composition to the clutter, and order to chaos. These objects alone have no significance, but when portrayed together they tell a compelling story, if not a biography. In much the same way, blankets are blankets until viewed through another lens. What is ordinary changes simply because we are looking. And when we are looking, we begin to see the many different sides of a thing, and what the multiplied semiotics of that thing can be.

Jasper Johns spoke frequently to the duality in his work. He said:

I made the flags and targets to open men’s eyes … (they) were both things - which are seen and not looked at - examined.

We expect artists to exist in a dynamic, rather than a static state. We expect them to respond to their environment and a constant stream of input and information. Continuity is a throughline of stories and meaning embedded deep within the artist’s underlying philosophy. The artists themselves are the binding thread across time and in their own work, creating the material conditions to tell a cohesive story. Therefore, artists must allow themselves duality and contradiction - I am this, I am not this, I am these things. It speaks to their unspeakable compulsion to make things in spite of all the odds, in spite of oppression, whatever those things may be; however those things must be.

True to the meaning and purpose of love letters, Joey Veltkamp’s duality is sweet, nostalgic, and celebratory. Like a rush of blood to the head we are dizzy with color, joy, and happiness. Of course there is context, meaning, and a story Veltkamp wants to tell us, but he doesn’t tell it for us. His view is only a window into a world he is willing to share and we are allowed to move through it and place ourselves within it. He has created a space to live and move with us, wherever we go.

We carry it, like a pocket full of love letters.

Jasper Johns spoke frequently to the duality in his work. He said:

I made the flags and targets to open men’s eyes … (they) were both things - which are seen and not looked at - examined.

We expect artists to exist in a dynamic, rather than a static state. We expect them to respond to their environment and a constant stream of input and information. Continuity is a throughline of stories and meaning embedded deep within the artist’s underlying philosophy. The artists themselves are the binding thread across time and in their own work, creating the material conditions to tell a cohesive story. Therefore, artists must allow themselves duality and contradiction - I am this, I am not this, I am these things. It speaks to their unspeakable compulsion to make things in spite of all the odds, in spite of oppression, whatever those things may be; however those things must be.

True to the meaning and purpose of love letters, Joey Veltkamp’s duality is sweet, nostalgic, and celebratory. Like a rush of blood to the head we are dizzy with color, joy, and happiness. Of course there is context, meaning, and a story Veltkamp wants to tell us, but he doesn’t tell it for us. His view is only a window into a world he is willing to share and we are allowed to move through it and place ourselves within it. He has created a space to live and move with us, wherever we go.

We carry it, like a pocket full of love letters.