EMILY GHERARD \ IT ALL BURNS

SHARON ARNOLD

NOVEMBER 2017

This November, Bridge Productions is pleased to announce the return of Seattle-based painter, draughtsman, and printmaker Emily Gherard. Gherard is best known for her powerfully physical paintings and works on paper, built from the accumulation and erosion of repetitive mark-making in charcoal, graphite, acrylic, and oil. Tearing, scratching, and sanding the surface onto which she continually adds material, Gherard builds up a physicality which brings tangible weight and gravity to her pieces. For her latest body of work in It All Burns, Emily Gherard presents a series of new paintings which continue her pursuit of figuratively evocative abstraction, as well as a series of scored graphite drawings on a new material, rubber.

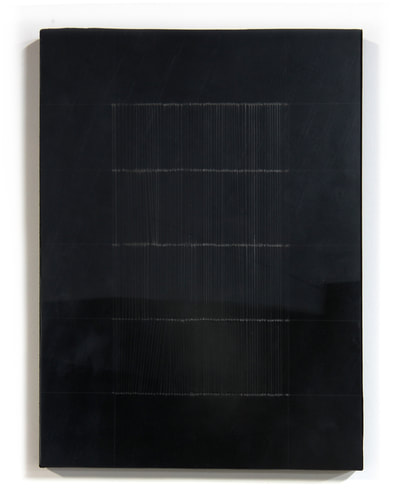

This new exploration is enacted by rubbing graphite powder onto the surface of rubber panels, which have been engraved and pierced with a graphite pencil. The effect is a ruddy metallic sheen which interacts with and thwarts the glossy, reflective nature of the material; bringing forward the cuneiform-like etchings, dots, and gridded lines of the pencil. These works are related to a kind of action painting; made quickly, directly, and intuitively. The compositions are similar across the series but each unique graph, cipher, and code presents its own storied pattern. They speak to centuries of linguistic systems employed for recording, documenting, and archiving and elude to a mysterious but specific order and methodology.

In her previous solo exhibition, Making Presence Known, Gherard focused on smaller pieces which embodied an idea of closeness, intimacy, and what the hand could hold. The works in the show were layered, dark and metallic, meticulously glazed with graphite washes and an oily sheen that required a personal close-up view. But Gherard also left us with two distinctive, hovering, and glowing works which hinted at a return to ghostly, obscured figures amidst a pixelated haze. These larger paintings were made with a fluorescent orange-red imprimatura which extended around to the sides and backs of their panels, emitting a bright glow from the light reflecting off the wall behind them. This glow extended the painting’s presence to be larger than they appeared, heightening a sense of eminence. The glow itself also suggested a fire within, the kind of heat that only comes after the embers have burned at their hottest beneath the flame.

It All Burns features paintings which feel as if they've been exposed to fire and smoke, revealing slightly charred and scorched blocks of composition. They exude a feeling of exhaustion and gravity, not just from the labor of their making but in their projection of weight and fatigue. The fluorescent emanation from within and behind the work suggests there is still a brilliant, contained energy beneath the weariness and ashen exterior. Looking closer, we can see a discernible fiery ember emerging from beneath the black exterior. The figure is neither dead nor diminished but in retreat; burdened to the point of collapse but still lit from within. Like a molten pool of lava below the earth’s fallow crust, a regeneration is taking place which can only result in a pyroclastic explosion; the inevitable result of imposed tension and restraint.

One painting in particular speaks to this feeling of bearing an untenable crushing load. Gherard’s painting titled The Blind Leading the Blind is based on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting of the same name, in which figures descend into chaos from one side of the canvas to the other. In Gherard’s piece, the composition mirror’s Bruegel’s, her shadowy blocks echoing the figures as they fall, crumbling and dissolving towards the bottom edge. The forms are thin and pale. The destruction of these cascading forms reveal more of an implied reality occurring beneath the surface; subtle and insipid. Violent, and dangerous. Sorrowful.

Bruegel’s piece may have been a reflection of the political turmoil of his time. Prior to his painting The Blind Leading the Blind, the Council of Troubles were established, a tribunal formed for the express purpose of punishing political and religious leaders inciting provocation in the Spanish Netherlands. The Council was behind so many mass arrests and executions it became known as the Council of Blood. Currently, in the United States, our Administration unseats itself and us on a daily basis; throwing civil liberties, civil rights, immigrant rights, healthcare, and political stability in all executive branches into express peril.

Both Breugel’s and Gherard’s paintings embody periods of great change, unrest, and uncertainty in their time. Their compositions illustrate an imbalanced, chaotic, crumbling imbalance that empathetic souls will recognize. As Gherard’s ongoing narrative has been built around a making the indelible unknown relatably human, the narrative she builds allows the viewer to empathize, projecting themselves into the image as though they, themselves, are the subject. Large silhouettes stack up and recede into the distance, rising and falling, crumbling into the foreground or cascading into the darkness below like a flowing cataract. Like their real-world counterparts—like us—the forms stand in defiance of their environments, even as they are being shaped by them.

Emily Gherard is a Seattle-based painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. She received her MFA from the University of Washington, and her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Gherard is best known for her powerfully physical paintings and works on paper, built from the accumulation and erosion of repetitive mark-making in charcoal, graphite, acrylic, and oil. Tearing, scratching, and sanding the surface onto which she continually adds material, Gherard builds up a physicality which brings tangible weight and gravity to her work; making the indelible unknown relatably human. Gherard has was represented by Bridge Productions at the Seattle Art Fair in both 2017 and 2016; and has been featured at SOIL, Hedreen Gallery, Gallery 4Culture, The Museum of Northwest Art, Francine Seders Gallery, Cornish College of the Arts, Blindfold Gallery, and The Henry Art Gallery. She received the 2006 PONCHO Special Recognition Award and a 2014 GAP Grant. She was finalist for the 2006 and 2010 Betty Bowen Award, a painting finalist for the 2013 Neddy Art Awards at Cornish, and a Stranger Magazine Genius Nominee for in Visual Art in 2014. She has taught for the last ten years throughout the Puget Sound area, including North Seattle College, Everett Community College, Bellevue College, and Western Washington University. Emily is represented by Bridge Productions in Seattle, Washington.

This new exploration is enacted by rubbing graphite powder onto the surface of rubber panels, which have been engraved and pierced with a graphite pencil. The effect is a ruddy metallic sheen which interacts with and thwarts the glossy, reflective nature of the material; bringing forward the cuneiform-like etchings, dots, and gridded lines of the pencil. These works are related to a kind of action painting; made quickly, directly, and intuitively. The compositions are similar across the series but each unique graph, cipher, and code presents its own storied pattern. They speak to centuries of linguistic systems employed for recording, documenting, and archiving and elude to a mysterious but specific order and methodology.

In her previous solo exhibition, Making Presence Known, Gherard focused on smaller pieces which embodied an idea of closeness, intimacy, and what the hand could hold. The works in the show were layered, dark and metallic, meticulously glazed with graphite washes and an oily sheen that required a personal close-up view. But Gherard also left us with two distinctive, hovering, and glowing works which hinted at a return to ghostly, obscured figures amidst a pixelated haze. These larger paintings were made with a fluorescent orange-red imprimatura which extended around to the sides and backs of their panels, emitting a bright glow from the light reflecting off the wall behind them. This glow extended the painting’s presence to be larger than they appeared, heightening a sense of eminence. The glow itself also suggested a fire within, the kind of heat that only comes after the embers have burned at their hottest beneath the flame.

It All Burns features paintings which feel as if they've been exposed to fire and smoke, revealing slightly charred and scorched blocks of composition. They exude a feeling of exhaustion and gravity, not just from the labor of their making but in their projection of weight and fatigue. The fluorescent emanation from within and behind the work suggests there is still a brilliant, contained energy beneath the weariness and ashen exterior. Looking closer, we can see a discernible fiery ember emerging from beneath the black exterior. The figure is neither dead nor diminished but in retreat; burdened to the point of collapse but still lit from within. Like a molten pool of lava below the earth’s fallow crust, a regeneration is taking place which can only result in a pyroclastic explosion; the inevitable result of imposed tension and restraint.

One painting in particular speaks to this feeling of bearing an untenable crushing load. Gherard’s painting titled The Blind Leading the Blind is based on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting of the same name, in which figures descend into chaos from one side of the canvas to the other. In Gherard’s piece, the composition mirror’s Bruegel’s, her shadowy blocks echoing the figures as they fall, crumbling and dissolving towards the bottom edge. The forms are thin and pale. The destruction of these cascading forms reveal more of an implied reality occurring beneath the surface; subtle and insipid. Violent, and dangerous. Sorrowful.

Bruegel’s piece may have been a reflection of the political turmoil of his time. Prior to his painting The Blind Leading the Blind, the Council of Troubles were established, a tribunal formed for the express purpose of punishing political and religious leaders inciting provocation in the Spanish Netherlands. The Council was behind so many mass arrests and executions it became known as the Council of Blood. Currently, in the United States, our Administration unseats itself and us on a daily basis; throwing civil liberties, civil rights, immigrant rights, healthcare, and political stability in all executive branches into express peril.

Both Breugel’s and Gherard’s paintings embody periods of great change, unrest, and uncertainty in their time. Their compositions illustrate an imbalanced, chaotic, crumbling imbalance that empathetic souls will recognize. As Gherard’s ongoing narrative has been built around a making the indelible unknown relatably human, the narrative she builds allows the viewer to empathize, projecting themselves into the image as though they, themselves, are the subject. Large silhouettes stack up and recede into the distance, rising and falling, crumbling into the foreground or cascading into the darkness below like a flowing cataract. Like their real-world counterparts—like us—the forms stand in defiance of their environments, even as they are being shaped by them.

Emily Gherard is a Seattle-based painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. She received her MFA from the University of Washington, and her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design. Gherard is best known for her powerfully physical paintings and works on paper, built from the accumulation and erosion of repetitive mark-making in charcoal, graphite, acrylic, and oil. Tearing, scratching, and sanding the surface onto which she continually adds material, Gherard builds up a physicality which brings tangible weight and gravity to her work; making the indelible unknown relatably human. Gherard has was represented by Bridge Productions at the Seattle Art Fair in both 2017 and 2016; and has been featured at SOIL, Hedreen Gallery, Gallery 4Culture, The Museum of Northwest Art, Francine Seders Gallery, Cornish College of the Arts, Blindfold Gallery, and The Henry Art Gallery. She received the 2006 PONCHO Special Recognition Award and a 2014 GAP Grant. She was finalist for the 2006 and 2010 Betty Bowen Award, a painting finalist for the 2013 Neddy Art Awards at Cornish, and a Stranger Magazine Genius Nominee for in Visual Art in 2014. She has taught for the last ten years throughout the Puget Sound area, including North Seattle College, Everett Community College, Bellevue College, and Western Washington University. Emily is represented by Bridge Productions in Seattle, Washington.