THE WORDLESS GIVEN FORM

Sharon Arnold

September 2013

This essay is from the catalog for Jennifer McNeely's solo exhibition, Into the Deep.

In 2005, just back from New York, I was meandering through the TK Building in Pioneer Square - a building in Seattle’s historic gallery district which houses a few dozen galleries and artist studios on the ground floor, and artist live/work spaces above. I remember the excitement I felt as I discovered strong contemporary work in galleries like Punch, 4Culture, G. Gibson, and SOIL. Next to SOIL was a particularly eye-catching gallery called Platform Gallery (all of these galleries still occupy their spaces today), which was curated by four artists: Stephon Lyons, Carol Bolt, Blake Haygood, and Dirk Park. Today, the gallery is run solely by Stephon Lyons, whose elegant and thoughtful aesthetic prevails.

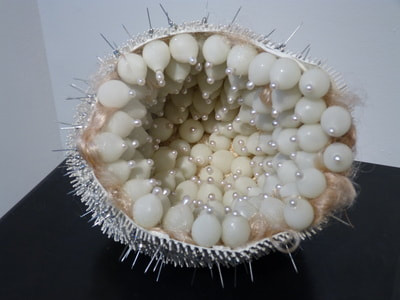

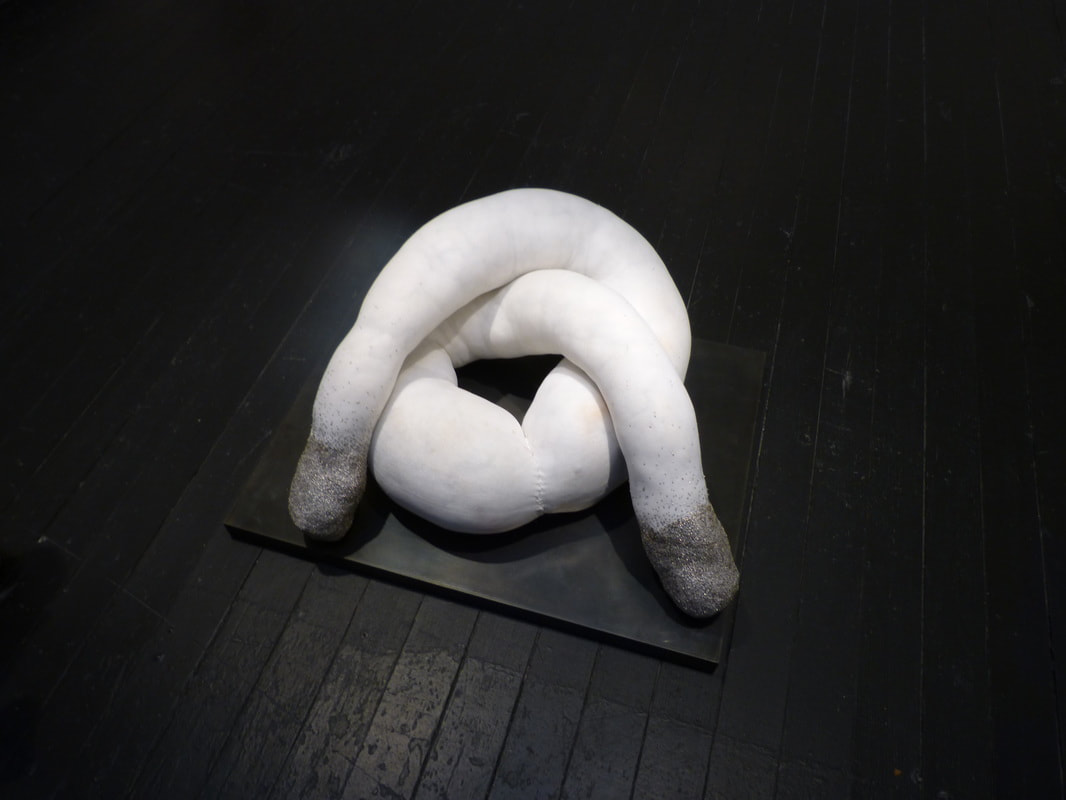

It was this same year that Jennifer McNeely’s solo exhibition at Platform stopped me in my tracks. The gallery was completely overgrown with bulbous, fruit-like sexual forms made of cloth, nylons, coupled bra cups, and fur lewdly poking out of various folds. Chains of seaweed-like clustered nodules hung from the the wall to trail across the floor. It was all I could do to not touch them, rub my cheek against the rabbit fur, or burst into tears because some odd-shaped emotion that had to do with my odd-shaped parts had finally come to light. If Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse are the embodiment of all that is wordless given form, then McNeely is surely their successor in this wordless language.

McNeely's legacy of Sisyphean ritualistic preverbal art-making seems to include a compulsion to repair. This renovation is arbitrary – the materials don’t seem to originate as ripped, torn, or otherwise ruined objects; it is the superfluous mending of these objects which requires no fortification other than one the artist desires. The artist is both weakening and strengthening a material that previous to the process was whole and undamaged. The process itself creates something new out of the formerly undamaged/damaged/mended object.

Is it pointless to restore materials which for all intents and purposes are perfectly fine to begin with? How does this process relate to the endless toil of “women’s work”; the specific acts of homemaking, needlecraft, maintenance, and caretaking (a man will work from dusk to dawn, but a woman's work is never done)? McNeely admits that her work is precisely, continually, about refurbishment and the old made new again. She also happens to work with traditionally feminine materials: cloth, upholstery, medical dressings, personal beauty-related objects, thread, and yarn. Historically, women’s roles are behind the scenes; hidden away in hearth and home, schools, hospitals, or farms; submerging themselves in the mechanical workings of the task at hand. Women were generally expected to toil without credit or reward, while men gauged their identity by such recognition, and were applauded for it.

Yet McNeely’s work embodies all of these tropes and contradictions, whether masculine or feminine-identified, or through opposing materials. She toils relentlessly to drive her vision so that you will recognize the fruit of her labor and know her; and so she may heal.

It occurs to me that as I’ve struggled to write this essay, the wall I’ve hit has to do with my own history of arbitrary repair. Just prior to my return to art school, I lived through an event that inexplicably changed my inner and outer landscape. It was the catalyst that has shaped every choice I make now. In school, my work was made of delicate plaster shells sewn together in the shape of human bones and soaked in salt, piles of clumpy salt-crusted twine coiled on the floor beneath. This is where the repair began, though I wasn’t aware of it at the time. I sewed more bones together and connected them, soaking them in a heavy slurry of salt until the entire thing was crusted over, encased in the hardened brine. My mind and body does what it can with trauma but it’s a flawed device and a warped lens. Submerged in memory, I am in a constant state of repair.

Into the Deep implies another kind of submersion, though mimetically different than memory. Far below the surface of the earth’s oceans, at nearly unmarked depths, creatures exist in complete darkness. The pressure is so intense that you must have evolved to endure it. There is no light, taste, smell, and barely any sound. There is only feeling. Creatures are all cilium, flagellum, proboscis, and mouth. They live to survive; against the current, against all odds.

McNeely willingly exposes herself to this harsh climate to feel her way in the dark. In lieu of her body, she has created preverbal representatives to go forth and explore the depths in her stead. She outfits her flora and fauna with the parts they need to survive the viscous stew. They are curled, tubed, nippled, tentacled, fringed, and bulbous. Some are meant to float atop the surface – their mammillary protrusions are either subconscious manifestations of Artemis, or they are the bodies, bladders, blades, and clusters of abundantly fruited seaweed. These proxies travel where she cannot go. They feel what she can’t. They give her release.

For us, these creatures and forms provide a mirror to examine the shape of our own inner oceanic dwellers. If there is a crack through which we can feel wonder, delight, joy, sadness, love, labor, or yes even beauty; McNeely has broken it wide open. We are rewarded with not just feeling, but vision - out of the deep, and in the light of day.

In 2005, just back from New York, I was meandering through the TK Building in Pioneer Square - a building in Seattle’s historic gallery district which houses a few dozen galleries and artist studios on the ground floor, and artist live/work spaces above. I remember the excitement I felt as I discovered strong contemporary work in galleries like Punch, 4Culture, G. Gibson, and SOIL. Next to SOIL was a particularly eye-catching gallery called Platform Gallery (all of these galleries still occupy their spaces today), which was curated by four artists: Stephon Lyons, Carol Bolt, Blake Haygood, and Dirk Park. Today, the gallery is run solely by Stephon Lyons, whose elegant and thoughtful aesthetic prevails.

It was this same year that Jennifer McNeely’s solo exhibition at Platform stopped me in my tracks. The gallery was completely overgrown with bulbous, fruit-like sexual forms made of cloth, nylons, coupled bra cups, and fur lewdly poking out of various folds. Chains of seaweed-like clustered nodules hung from the the wall to trail across the floor. It was all I could do to not touch them, rub my cheek against the rabbit fur, or burst into tears because some odd-shaped emotion that had to do with my odd-shaped parts had finally come to light. If Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse are the embodiment of all that is wordless given form, then McNeely is surely their successor in this wordless language.

McNeely's legacy of Sisyphean ritualistic preverbal art-making seems to include a compulsion to repair. This renovation is arbitrary – the materials don’t seem to originate as ripped, torn, or otherwise ruined objects; it is the superfluous mending of these objects which requires no fortification other than one the artist desires. The artist is both weakening and strengthening a material that previous to the process was whole and undamaged. The process itself creates something new out of the formerly undamaged/damaged/mended object.

Is it pointless to restore materials which for all intents and purposes are perfectly fine to begin with? How does this process relate to the endless toil of “women’s work”; the specific acts of homemaking, needlecraft, maintenance, and caretaking (a man will work from dusk to dawn, but a woman's work is never done)? McNeely admits that her work is precisely, continually, about refurbishment and the old made new again. She also happens to work with traditionally feminine materials: cloth, upholstery, medical dressings, personal beauty-related objects, thread, and yarn. Historically, women’s roles are behind the scenes; hidden away in hearth and home, schools, hospitals, or farms; submerging themselves in the mechanical workings of the task at hand. Women were generally expected to toil without credit or reward, while men gauged their identity by such recognition, and were applauded for it.

Yet McNeely’s work embodies all of these tropes and contradictions, whether masculine or feminine-identified, or through opposing materials. She toils relentlessly to drive her vision so that you will recognize the fruit of her labor and know her; and so she may heal.

It occurs to me that as I’ve struggled to write this essay, the wall I’ve hit has to do with my own history of arbitrary repair. Just prior to my return to art school, I lived through an event that inexplicably changed my inner and outer landscape. It was the catalyst that has shaped every choice I make now. In school, my work was made of delicate plaster shells sewn together in the shape of human bones and soaked in salt, piles of clumpy salt-crusted twine coiled on the floor beneath. This is where the repair began, though I wasn’t aware of it at the time. I sewed more bones together and connected them, soaking them in a heavy slurry of salt until the entire thing was crusted over, encased in the hardened brine. My mind and body does what it can with trauma but it’s a flawed device and a warped lens. Submerged in memory, I am in a constant state of repair.

Into the Deep implies another kind of submersion, though mimetically different than memory. Far below the surface of the earth’s oceans, at nearly unmarked depths, creatures exist in complete darkness. The pressure is so intense that you must have evolved to endure it. There is no light, taste, smell, and barely any sound. There is only feeling. Creatures are all cilium, flagellum, proboscis, and mouth. They live to survive; against the current, against all odds.

McNeely willingly exposes herself to this harsh climate to feel her way in the dark. In lieu of her body, she has created preverbal representatives to go forth and explore the depths in her stead. She outfits her flora and fauna with the parts they need to survive the viscous stew. They are curled, tubed, nippled, tentacled, fringed, and bulbous. Some are meant to float atop the surface – their mammillary protrusions are either subconscious manifestations of Artemis, or they are the bodies, bladders, blades, and clusters of abundantly fruited seaweed. These proxies travel where she cannot go. They feel what she can’t. They give her release.

For us, these creatures and forms provide a mirror to examine the shape of our own inner oceanic dwellers. If there is a crack through which we can feel wonder, delight, joy, sadness, love, labor, or yes even beauty; McNeely has broken it wide open. We are rewarded with not just feeling, but vision - out of the deep, and in the light of day.