PATRICK KELLY \ IN TIME

Sharon Arnold

August 2017

This curatorial essay is the documentation from In Time, a solo exhibition of new work by Portland artist Patrick Kelly.

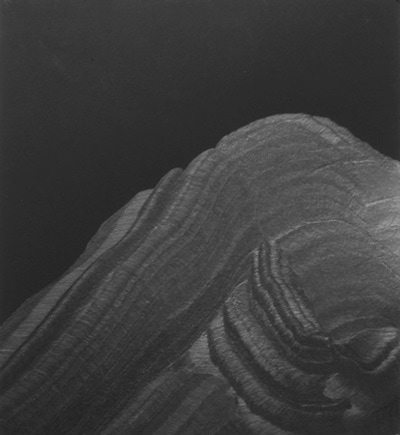

Patrick Kelly’s ongoing series of graphite drawings reference the mineral’s crystalline origins, as well as patterns in hematite or obsidian deposits. Their layered construction is a laborious process—Kelly hand-draughts an accumulative form made of jagged overlapping lines, assisted by a jig or stencil of his own design. The resulting effect is an opalescent black mass that shimmers and reflects the light, creating the illusion of a sculptural object in relief on flat paper. For In Time, Kelly's series of new works, he deals with the 18th century philosophical concept of "deep time", noting the exceptionally Sublime nature of geological creation over millennia in relationship to the brief span of a human life; and the profound, indelible mark of our impact on the earth.

A few past philosophers and scientists have concluded the earth is formed over an incomprehensible duration. Avicenna or Ibn Sīnā, a significant contributor to the Islamic Golden Age in the 10th century; and Shen Kuo, a multidisciplinary scientist and statesman in the 11th century during the Song Dynasty, both contributed detailed observational theories about the material evolution of the earth over millennia. In The Book of Healing, Ibn Sīnā wrote that the formations of mountains had to either be created through the movement of the Earth's crust, such as an earthquake; or through the erosive quality of water which created valleys, revealing strata of various types. His suggestion was ultimately that either formation required such a long period of time that the mountains would by now be eroded. In his observation of the strata of a mountain range, Shen Kuo marine noted fossils hundreds of miles inland from the ocean as well as bamboo deposits in climates where it didn't grow, and hypothesized that geologic shifts were created in part through the erosion of surface land formations that revealed older ones beneath them. In doing so, he suggested that the formation of the continent had to occur over an incredible duration of time. In considering the way their respective mountainous regions simultaneously pushed up and obscured the land, they concluded these formations could have only occurred over an epoch far longer than the reach of human history.

Patrick cites a much later European progenitor of similar ideas was 18th century, Scottish geologist James Hutton. While studying the relationship between layers of rock in Scotland’s Siccar Point, Hutton observed structures of angular unconformity in lines and layers of strata, which informed his notion that the earth was built up in accumulations and deposits made across aeons. His observations evolved into a hypothesis that the obduction of earth rotated around cycles of rock formed beneath the ocean then becoming uplifted or revealed, and inevitably eroding into small particles which made their way back to the sea. He remarked, “the mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time”. This statement suggested the human mind struggles to grapple with the awe-striking vastness of geological eras. Expounding further on its unfathomable nature, he continued to say "we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end".

The span of a human life, and all it creates, is far too brief a glimmer to truly understand and describe Sublime concepts of deep time. Yet our desire to emulate it persists. Our fascination with the laborious process of conceptualizing and making objects resists the temporal, rapid nature of our post-internet climate. While the digital mark is no less an impact, and our virtual storage increases to house its voluminous nature; our compulsion to make physical marks on concrete surfaces transcends our contemporary life span, persisting across millennia. A material deposit is the record of our presence, evidence of our hand, a translation of our voice; a story. As petroglyphs and paintings have shown us, deeply embedded onto the surface of rocks and inscribed onto walls in ancient caves, the handmade mark reaches across an eternity to tell our history.

Each of Kelly’s graphite lines tell a story, viscerally recording their making as concretely layered deposits, much like the rocks and minerals they come from. As laborious as these actions are, they are a mere echo of the structures architected in the expanse of geologic formation. Kelly’s intense process builds itself around a language of extreme physicality, echoing the methodical pace of tectonic forces in comparative hyperspeed. In building up, covering, and unearthing material, he recreates the eruption and erosion of angular unconformity. We observe each glint of soft metallic variances and opalescent sheen, considering the extent it took in its making; pondering the length of creation—of both natural and manmade forces— and we imagine the imperceptible shift of the earth beneath our feet, giddy from having peered so deeply into the abyss of time.

Patrick Kelly lives and works in Portland, Oregon. He received an MFA in 2005 from The George Washington University in Washington DC and has been showing work in Portland and New York; and in Seattle he’s been featured at Vermillion, Out of Sight, and Bridge Productions. Kelly’s work has been written about by John Motley for The Oregonian and is included in collections at the MoMA Library, New York, NY and the Bieneke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale, New Haven, CT. He was awarded a commission through Oregon Arts Commission to create work for Eastern Oregon University in their newly renovated Pierce Library.

Patrick Kelly’s ongoing series of graphite drawings reference the mineral’s crystalline origins, as well as patterns in hematite or obsidian deposits. Their layered construction is a laborious process—Kelly hand-draughts an accumulative form made of jagged overlapping lines, assisted by a jig or stencil of his own design. The resulting effect is an opalescent black mass that shimmers and reflects the light, creating the illusion of a sculptural object in relief on flat paper. For In Time, Kelly's series of new works, he deals with the 18th century philosophical concept of "deep time", noting the exceptionally Sublime nature of geological creation over millennia in relationship to the brief span of a human life; and the profound, indelible mark of our impact on the earth.

A few past philosophers and scientists have concluded the earth is formed over an incomprehensible duration. Avicenna or Ibn Sīnā, a significant contributor to the Islamic Golden Age in the 10th century; and Shen Kuo, a multidisciplinary scientist and statesman in the 11th century during the Song Dynasty, both contributed detailed observational theories about the material evolution of the earth over millennia. In The Book of Healing, Ibn Sīnā wrote that the formations of mountains had to either be created through the movement of the Earth's crust, such as an earthquake; or through the erosive quality of water which created valleys, revealing strata of various types. His suggestion was ultimately that either formation required such a long period of time that the mountains would by now be eroded. In his observation of the strata of a mountain range, Shen Kuo marine noted fossils hundreds of miles inland from the ocean as well as bamboo deposits in climates where it didn't grow, and hypothesized that geologic shifts were created in part through the erosion of surface land formations that revealed older ones beneath them. In doing so, he suggested that the formation of the continent had to occur over an incredible duration of time. In considering the way their respective mountainous regions simultaneously pushed up and obscured the land, they concluded these formations could have only occurred over an epoch far longer than the reach of human history.

Patrick cites a much later European progenitor of similar ideas was 18th century, Scottish geologist James Hutton. While studying the relationship between layers of rock in Scotland’s Siccar Point, Hutton observed structures of angular unconformity in lines and layers of strata, which informed his notion that the earth was built up in accumulations and deposits made across aeons. His observations evolved into a hypothesis that the obduction of earth rotated around cycles of rock formed beneath the ocean then becoming uplifted or revealed, and inevitably eroding into small particles which made their way back to the sea. He remarked, “the mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time”. This statement suggested the human mind struggles to grapple with the awe-striking vastness of geological eras. Expounding further on its unfathomable nature, he continued to say "we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end".

The span of a human life, and all it creates, is far too brief a glimmer to truly understand and describe Sublime concepts of deep time. Yet our desire to emulate it persists. Our fascination with the laborious process of conceptualizing and making objects resists the temporal, rapid nature of our post-internet climate. While the digital mark is no less an impact, and our virtual storage increases to house its voluminous nature; our compulsion to make physical marks on concrete surfaces transcends our contemporary life span, persisting across millennia. A material deposit is the record of our presence, evidence of our hand, a translation of our voice; a story. As petroglyphs and paintings have shown us, deeply embedded onto the surface of rocks and inscribed onto walls in ancient caves, the handmade mark reaches across an eternity to tell our history.

Each of Kelly’s graphite lines tell a story, viscerally recording their making as concretely layered deposits, much like the rocks and minerals they come from. As laborious as these actions are, they are a mere echo of the structures architected in the expanse of geologic formation. Kelly’s intense process builds itself around a language of extreme physicality, echoing the methodical pace of tectonic forces in comparative hyperspeed. In building up, covering, and unearthing material, he recreates the eruption and erosion of angular unconformity. We observe each glint of soft metallic variances and opalescent sheen, considering the extent it took in its making; pondering the length of creation—of both natural and manmade forces— and we imagine the imperceptible shift of the earth beneath our feet, giddy from having peered so deeply into the abyss of time.

Patrick Kelly lives and works in Portland, Oregon. He received an MFA in 2005 from The George Washington University in Washington DC and has been showing work in Portland and New York; and in Seattle he’s been featured at Vermillion, Out of Sight, and Bridge Productions. Kelly’s work has been written about by John Motley for The Oregonian and is included in collections at the MoMA Library, New York, NY and the Bieneke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale, New Haven, CT. He was awarded a commission through Oregon Arts Commission to create work for Eastern Oregon University in their newly renovated Pierce Library.