CALL AND RESPONSE: THE DUWAMISH RIVER ARTIST RESIDENCY

Catalogue essay for the group show, Process and Artifacts at Gallery 4Culture

Sharon Arnold

How many of us think of Seattle as home to a river?

The Duwamish River, flowing through the southern and southwestern reaches of Seattle, is out of sight to many city dwellers on a day-to-day basis. But it’s there, threading its body through the valleys of our industrial districts; its mouth yawning through bridges and around shipyards to pour itself into Elliott Bay.

The Duwamish has been shaped by humans, and its course changed over time. It is still wild in parts, in spite of urban development, holding some small refuge for birds of prey, waterfowl, fish, and a few mammals. As an estuary, it was once home to a complex ecosystem of this kind of wildlife and humans; a resident population of cedars, firs, and alders flanking its shores alongside tideflats, swamps, forest, and wetlands. It is named after the indigenous people, the Dkhw'Duw'Absh, People of the Inside, who populate this region around the river and Elliott Bay and Lake Washington, and who are still fighting for federal recognition of their tribe.

This river represents the duality of both timelessness and change. It flows, relentlessly, through land and through time. It rises, falls, and shifts color depending on the season and the weather. And though it no longer meanders, its path is now held by the walls of its industrial bed and the manufactured island splitting its delta. No longer flanked by a forest of native deciduous and evergreen trees, it is adorned with great cranes, container ships, and industrial warehouses.

As an entity, the Duwamish is an abstract idea: a historical artifact, a superfund site, an unrecognized people, a thing that is largely present and yet invisible. Ask a portion of the population what comes to mind when they think of Duwamish and most will say dirty water. Even fewer will name the local tribe after which the river is named and their displacement, or the industry that has replaced the forests, wildlife, and people. Much of Seattle’s historic and present-day trade is seated here: shipyards, steel mills, foundries, steam plants, rail lines, container yards, the Port of Seattle, Boeing, cargo terminals, commercial moorage, garbage and recycle facilities, the Department of Homeland Security, and a few cruise ships. And to others still, the Duwamish is home to neighborhoods like Georgetown, South Park, and Allentown. Nestled in the curves of its banks, these neighborhoods portray a rare urban environment: river life, complete with docks, rowboats, fishermen, and summertime swims.

This begins to give shape to the abstraction of a river. This river we can see but not see. This river that we know of, but don’t know. How do we come to see and know a river?

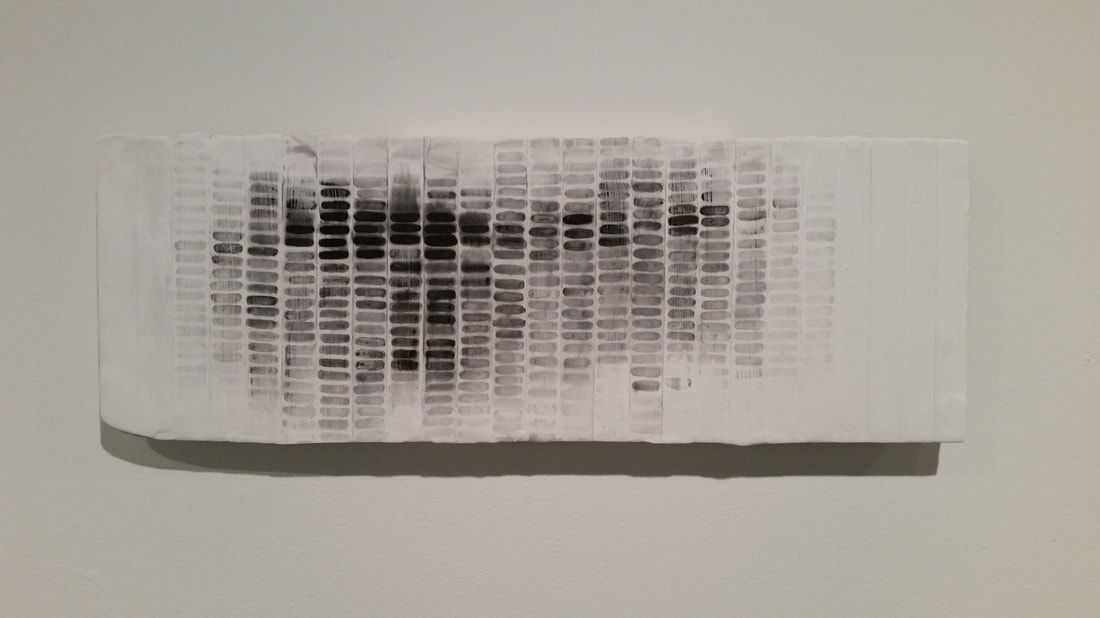

In Process and Artifacts at Gallery 4Culture, the twelve artists of the Duwamish River Artist Residency reveal their vision of the river when they’re working along its shores, hiking through green spaces, sketching among abandoned warehouses, and shooting film from across its bridges. Through their plein-air studies, landscape drawings and paintings, abstractions, rubbings, photographs, and observations of life along the river we begin to see this underrepresented region in a new way. Their bond with this untouristed district of the city is evident in their growing visual language around the river’s history and ecology.

What I felt strongly while viewing the collection of work from the Residency was an underlying connection and response to the enduring nature of the river, the objects alongside it, the blurring of past and present (as in I could not identify a specific time), the relentless flow and movement of the river, the light, the angles, and the color. There is a kind of quiet peaceful nature to this secret revealed through artist eyes. Each piece is like a stolen moment that if not documented, would slip past like a current in the river itself.

The work throughout this exhibition reflects the nature of the Duwamish River’s flux and feeling of lapsed time. It deftly captures this cinéma-vérité, which could be any point in time, not necessarily now, but also past and future. There are recursions in the entire collection of work throughout Process and Artifacts—patterns in composition, negative space, and form. Some pieces form a grid, alluding to the surrounding city blocks; and some exist in resolute denial of it. The artists reference nature, or industry, without falling into a precise narrative about either but instead pulling forward a tactile feeling of the place. The resulting artifacts leave us with a reflection of the timeless pattern of life along a river, looping back into itself, as we loop back around to it.

The river calls, and we respond.

The Duwamish River, flowing through the southern and southwestern reaches of Seattle, is out of sight to many city dwellers on a day-to-day basis. But it’s there, threading its body through the valleys of our industrial districts; its mouth yawning through bridges and around shipyards to pour itself into Elliott Bay.

The Duwamish has been shaped by humans, and its course changed over time. It is still wild in parts, in spite of urban development, holding some small refuge for birds of prey, waterfowl, fish, and a few mammals. As an estuary, it was once home to a complex ecosystem of this kind of wildlife and humans; a resident population of cedars, firs, and alders flanking its shores alongside tideflats, swamps, forest, and wetlands. It is named after the indigenous people, the Dkhw'Duw'Absh, People of the Inside, who populate this region around the river and Elliott Bay and Lake Washington, and who are still fighting for federal recognition of their tribe.

This river represents the duality of both timelessness and change. It flows, relentlessly, through land and through time. It rises, falls, and shifts color depending on the season and the weather. And though it no longer meanders, its path is now held by the walls of its industrial bed and the manufactured island splitting its delta. No longer flanked by a forest of native deciduous and evergreen trees, it is adorned with great cranes, container ships, and industrial warehouses.

As an entity, the Duwamish is an abstract idea: a historical artifact, a superfund site, an unrecognized people, a thing that is largely present and yet invisible. Ask a portion of the population what comes to mind when they think of Duwamish and most will say dirty water. Even fewer will name the local tribe after which the river is named and their displacement, or the industry that has replaced the forests, wildlife, and people. Much of Seattle’s historic and present-day trade is seated here: shipyards, steel mills, foundries, steam plants, rail lines, container yards, the Port of Seattle, Boeing, cargo terminals, commercial moorage, garbage and recycle facilities, the Department of Homeland Security, and a few cruise ships. And to others still, the Duwamish is home to neighborhoods like Georgetown, South Park, and Allentown. Nestled in the curves of its banks, these neighborhoods portray a rare urban environment: river life, complete with docks, rowboats, fishermen, and summertime swims.

This begins to give shape to the abstraction of a river. This river we can see but not see. This river that we know of, but don’t know. How do we come to see and know a river?

In Process and Artifacts at Gallery 4Culture, the twelve artists of the Duwamish River Artist Residency reveal their vision of the river when they’re working along its shores, hiking through green spaces, sketching among abandoned warehouses, and shooting film from across its bridges. Through their plein-air studies, landscape drawings and paintings, abstractions, rubbings, photographs, and observations of life along the river we begin to see this underrepresented region in a new way. Their bond with this untouristed district of the city is evident in their growing visual language around the river’s history and ecology.

What I felt strongly while viewing the collection of work from the Residency was an underlying connection and response to the enduring nature of the river, the objects alongside it, the blurring of past and present (as in I could not identify a specific time), the relentless flow and movement of the river, the light, the angles, and the color. There is a kind of quiet peaceful nature to this secret revealed through artist eyes. Each piece is like a stolen moment that if not documented, would slip past like a current in the river itself.

The work throughout this exhibition reflects the nature of the Duwamish River’s flux and feeling of lapsed time. It deftly captures this cinéma-vérité, which could be any point in time, not necessarily now, but also past and future. There are recursions in the entire collection of work throughout Process and Artifacts—patterns in composition, negative space, and form. Some pieces form a grid, alluding to the surrounding city blocks; and some exist in resolute denial of it. The artists reference nature, or industry, without falling into a precise narrative about either but instead pulling forward a tactile feeling of the place. The resulting artifacts leave us with a reflection of the timeless pattern of life along a river, looping back into itself, as we loop back around to it.

The river calls, and we respond.