BURDOCK

PLANT MEDICINE LAB MARCH 2020

Note: While the resources used are included at the bottom of the page, these monographs have been pulled from class lectures and currently lack in-line or numerical citations, and pages in the references. At some point I will come back and update these texts to include them.

HISTORIES & FOLKLORE

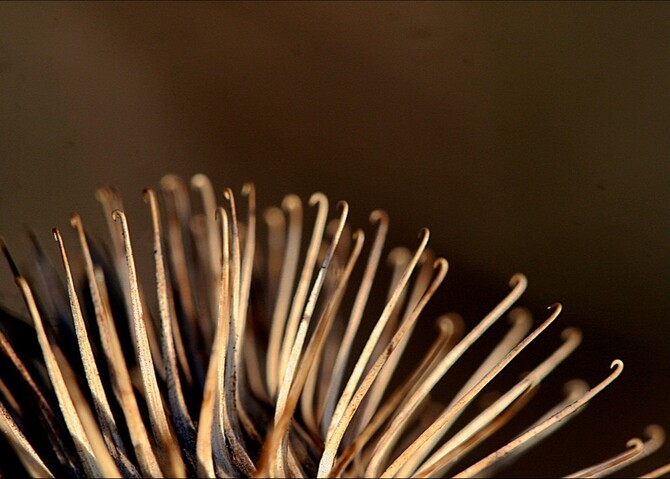

Articum lappa, commonly known as burdock, grows thistle-like flowers on long stalks up to nine feet in height. Burdock sends an enormous taproot into the ground and for this reason it presents a challenging harvest, as digging up the root is an effort! Its broad leaves are oval-shaped towards the top of the plant, gigantic and heart-shaped at the base. The foliage is a deep, dark green with a soft down on the undersides of the leaves, and the flowers themselves range from light or bright pink to purplish, appearing in the second year of the plant’s life. Many folks may only notice burdock when they realize they’ve collected burs on their coat or sweater. These are actually the rough, fuzzy fruit of the plant which contains the seeds— think of the burrs as spiky hitchhikers looking for a good spot to land! This is where the common name comes from, such as the French word bourre which indicates a "tangle of wool", and the German dock which refers generally to a multitude of plants with large leaves. Anglo Saxon names for Burdock were herrif, aireve, or airup, either from the noun for hoeg, a hedge, and reafe, a robber; or from the verb reafian, which means to seize. I personally enjoy this Gaelic phrase, Mac an dogha which means, "the mischievous plant" or the Welsh Cribe y bleidd, meaning "wolf's comb". The Greek word arctium comes from arctos which means "bear," and the Latin word, lappa means burr, barb, or thorn.

Fun fact: the invention of velcro is due to the Swiss inventor Georges de Mestral's interaction with burdock on a nature hike. He went home, examined the little hooks on the bur, and in 1955 released the hook-and-loop system that we still use today.

Burdock is native to Europe and Asia, and has naturalized across North America. While the use of its root is more widely known, many folk cures still employ the leaves as an ingredient in several remedies. Traditional uses throughout the world describe its application as useful for everything from internal digestive issues to relief for a multitude of skin conditions. The Anglo Saxons included burdock, called clate, as one of the many ingredients in “the green salve” of the Leechbook III, known for its healing properties. It was also said that clate was useful “against a sudden sickness,” boiled in ale with wenwort, bishopwort, fennel, and radish. And many other old European folk remedies include recipes for infusions or decoctions of the seeds; the root is used as a digestive aid; and the leaves can be used as a poultice. Brought to the US by the Germans, remedies can be found in various Pennsylvania Dutch curatives and recipes.

CULINARY USES

Bridging the use of burdock from medicinal to culinary history is an old English remedy known as a posset, a wine or ale decoction of both root and seeds to “wear down stones”, which we also find in Scotland and Ireland as well. It appears in manuscripts dating back to the 15th century, but in later records, the drink includes heated cream with eggs, honey, and various spices. Some recipes describe the cream as curdling, which does happen; and still others don't indicate curdling to appear. Possets are made in a specialized double-handled vessel, resembling a squat, square-bottomed teapot, to pour the decoction directly from the bottom of the pot. In some places, around the 16th century, posset shifted more towards a confectionery dessert now known as a “syllabub”, a name with no clear origin; or the better known cranachan in Scotland. The closest contemporary approximation we might have with this dessert is trifle or caudle (which by the way is also a medicine, as well as a ritual food at Beltane); or eggnog.

Dandelion & Burdock is a modern drink with roots as a light “hedgerow” mead, made from fermented dandelion in the Middle Ages, but which is now a popular soft drink across the United Kingdom. Before the widespread use of hops, similarly to mugwort, burdock was used as a bittering agent in beers across Europe. This demonstrates the various regional identities of beer according to their environment before mass production.

This recipe for a salad is an excerpt from A NEVV BOOKE of Cookerie by John Murrell, England, 1615:

A Sallet of Burdock rootes. Cut off the outward rinde, and lay them in water, a good houre at the least: when you haue done, seeth them vntill they be tender. Then set them on coles with Butter and Uinegar, and so let them stand a pretty while: then put in grated Bread and Sugar, betwixt euery lay, and serue them in.

This recipe demonstrates the way the root’s tough outer rind— which is black while the meat inside is white— is removed before it’s soaked to tenderize before cooking in butter and vinegar. Therefore we can see how it makes the most sense, for culinary purposes, to seek out tender spring shoots, stalks, and leaves in the plants' first year. These are best suited for eating but similarly to celery, the stalks' outer skin will need to be peeled before cooking. These can all be eaten raw, sautéed, blanched, or pickled depending on their intended use.

Known as gobō in Japan, niúbàng in Chinese, and u-eong in Korean; the root may be eaten either fresh or sautéed, and the leaves themselves are cooked the same as any other leafy green. Kinpira gobō is a dish in Japan in which burdock and carrot are finely sliced into thin strips and sautéed with sesame oil, soy sauce, sugar, and sake or mirin. Another popular dish is burdock makizushi, which is rice and pickled burdock root!

ESOTERICA

Burdock, called pitrack in Anatolia, is a common motif woven into Turkish, Persian, Iranian, or other Southwest and Central Asian kilims, which are flat hand-woven tapestry style carpets used for a variety of purposes from furnishing large rooms to individual use as prayer rugs. Burdock appears in these patterns as a symbol to ward against the evil eye—the belief comes from observing the way burdock burrs stick to people and leave the plant. But another facet of the symbol is due to its voluminous flower bundles, which represent abundance, and the symbol then serves as a blessing to the household. Therefore we see over a dozen different designs for these symbols varying across tribes, regions, and purposes; but each representing either a protective ward or a blessing for abundance.

The Anglo Saxons included clate, ie burdock root, specifically; as one of the many ingredients in “the green salve” of the Lacnunga, known for its healing properties. (The Lacnunga is a medical manuscript in which we find Anglo Saxon medical texts and remedies, charms, recipes and prayers) It was also said that clate was useful “against a sudden sickness,” boiled in ale with wenwort, bishopwort, fennel, and radish. It should be noted that healing in this context wasn’t separate from acts of magical work, hence why we’re adding this note here in this particular section. Salves in the Lacnunga are cited as a magical technology with a wide variety of practical applications. Cures were in this sense a critical part of spiritual hygiene and protection.

Burdock is one of the roots used in various traditions of carving protective objects, such as the alraun, in which the root is carved into a figure and put into a small box (sometimes fashioned as a small coffin) as a protective entity. Alrauns are most commonly made out of mandrake but several other roots, especially if forked and already resembling a figure, may be used. Alrauns are potent magic, not suggested as curiosities; and require lots of tending to and care. They can offer up great blessings, similar to poppets, when well nurtured.

Many people use burdock in the home to ward against negativity; such as casting it as a powder, especially around the corners of the home. It can be added to any incense or blend for protection as well. Some traditions call for cutting the root into small pieces which can then be strung like beads on red thread to wear around the wrist or the neck for protection against ill intent and negativity.

Across cultures it seems burdock is a powerfully apotropaic amulet and symbol; no doubt its positive effects as a healing agent as well as its naturally occurring characteristics (the burrs) are what draws forward its properties as a defensive agent. Use in amulets, potions, baths, washes; or as part of a ritual meal.

Note:

This monograph is adapted from a series of courses taught in 2019 and 2020 and part of a larger project about the use of herbs and woods in a few select European smoke and water practices. I've focused on these practices as a way to point towards some traditions we all have access too, and in the interest of peeling back a few layers onto why these herbs are so popular in our contemporary traditions, today.

Articum lappa, commonly known as burdock, grows thistle-like flowers on long stalks up to nine feet in height. Burdock sends an enormous taproot into the ground and for this reason it presents a challenging harvest, as digging up the root is an effort! Its broad leaves are oval-shaped towards the top of the plant, gigantic and heart-shaped at the base. The foliage is a deep, dark green with a soft down on the undersides of the leaves, and the flowers themselves range from light or bright pink to purplish, appearing in the second year of the plant’s life. Many folks may only notice burdock when they realize they’ve collected burs on their coat or sweater. These are actually the rough, fuzzy fruit of the plant which contains the seeds— think of the burrs as spiky hitchhikers looking for a good spot to land! This is where the common name comes from, such as the French word bourre which indicates a "tangle of wool", and the German dock which refers generally to a multitude of plants with large leaves. Anglo Saxon names for Burdock were herrif, aireve, or airup, either from the noun for hoeg, a hedge, and reafe, a robber; or from the verb reafian, which means to seize. I personally enjoy this Gaelic phrase, Mac an dogha which means, "the mischievous plant" or the Welsh Cribe y bleidd, meaning "wolf's comb". The Greek word arctium comes from arctos which means "bear," and the Latin word, lappa means burr, barb, or thorn.

Fun fact: the invention of velcro is due to the Swiss inventor Georges de Mestral's interaction with burdock on a nature hike. He went home, examined the little hooks on the bur, and in 1955 released the hook-and-loop system that we still use today.

Burdock is native to Europe and Asia, and has naturalized across North America. While the use of its root is more widely known, many folk cures still employ the leaves as an ingredient in several remedies. Traditional uses throughout the world describe its application as useful for everything from internal digestive issues to relief for a multitude of skin conditions. The Anglo Saxons included burdock, called clate, as one of the many ingredients in “the green salve” of the Leechbook III, known for its healing properties. It was also said that clate was useful “against a sudden sickness,” boiled in ale with wenwort, bishopwort, fennel, and radish. And many other old European folk remedies include recipes for infusions or decoctions of the seeds; the root is used as a digestive aid; and the leaves can be used as a poultice. Brought to the US by the Germans, remedies can be found in various Pennsylvania Dutch curatives and recipes.

CULINARY USES

Bridging the use of burdock from medicinal to culinary history is an old English remedy known as a posset, a wine or ale decoction of both root and seeds to “wear down stones”, which we also find in Scotland and Ireland as well. It appears in manuscripts dating back to the 15th century, but in later records, the drink includes heated cream with eggs, honey, and various spices. Some recipes describe the cream as curdling, which does happen; and still others don't indicate curdling to appear. Possets are made in a specialized double-handled vessel, resembling a squat, square-bottomed teapot, to pour the decoction directly from the bottom of the pot. In some places, around the 16th century, posset shifted more towards a confectionery dessert now known as a “syllabub”, a name with no clear origin; or the better known cranachan in Scotland. The closest contemporary approximation we might have with this dessert is trifle or caudle (which by the way is also a medicine, as well as a ritual food at Beltane); or eggnog.

Dandelion & Burdock is a modern drink with roots as a light “hedgerow” mead, made from fermented dandelion in the Middle Ages, but which is now a popular soft drink across the United Kingdom. Before the widespread use of hops, similarly to mugwort, burdock was used as a bittering agent in beers across Europe. This demonstrates the various regional identities of beer according to their environment before mass production.

This recipe for a salad is an excerpt from A NEVV BOOKE of Cookerie by John Murrell, England, 1615:

A Sallet of Burdock rootes. Cut off the outward rinde, and lay them in water, a good houre at the least: when you haue done, seeth them vntill they be tender. Then set them on coles with Butter and Uinegar, and so let them stand a pretty while: then put in grated Bread and Sugar, betwixt euery lay, and serue them in.

This recipe demonstrates the way the root’s tough outer rind— which is black while the meat inside is white— is removed before it’s soaked to tenderize before cooking in butter and vinegar. Therefore we can see how it makes the most sense, for culinary purposes, to seek out tender spring shoots, stalks, and leaves in the plants' first year. These are best suited for eating but similarly to celery, the stalks' outer skin will need to be peeled before cooking. These can all be eaten raw, sautéed, blanched, or pickled depending on their intended use.

Known as gobō in Japan, niúbàng in Chinese, and u-eong in Korean; the root may be eaten either fresh or sautéed, and the leaves themselves are cooked the same as any other leafy green. Kinpira gobō is a dish in Japan in which burdock and carrot are finely sliced into thin strips and sautéed with sesame oil, soy sauce, sugar, and sake or mirin. Another popular dish is burdock makizushi, which is rice and pickled burdock root!

ESOTERICA

Burdock, called pitrack in Anatolia, is a common motif woven into Turkish, Persian, Iranian, or other Southwest and Central Asian kilims, which are flat hand-woven tapestry style carpets used for a variety of purposes from furnishing large rooms to individual use as prayer rugs. Burdock appears in these patterns as a symbol to ward against the evil eye—the belief comes from observing the way burdock burrs stick to people and leave the plant. But another facet of the symbol is due to its voluminous flower bundles, which represent abundance, and the symbol then serves as a blessing to the household. Therefore we see over a dozen different designs for these symbols varying across tribes, regions, and purposes; but each representing either a protective ward or a blessing for abundance.

The Anglo Saxons included clate, ie burdock root, specifically; as one of the many ingredients in “the green salve” of the Lacnunga, known for its healing properties. (The Lacnunga is a medical manuscript in which we find Anglo Saxon medical texts and remedies, charms, recipes and prayers) It was also said that clate was useful “against a sudden sickness,” boiled in ale with wenwort, bishopwort, fennel, and radish. It should be noted that healing in this context wasn’t separate from acts of magical work, hence why we’re adding this note here in this particular section. Salves in the Lacnunga are cited as a magical technology with a wide variety of practical applications. Cures were in this sense a critical part of spiritual hygiene and protection.

Burdock is one of the roots used in various traditions of carving protective objects, such as the alraun, in which the root is carved into a figure and put into a small box (sometimes fashioned as a small coffin) as a protective entity. Alrauns are most commonly made out of mandrake but several other roots, especially if forked and already resembling a figure, may be used. Alrauns are potent magic, not suggested as curiosities; and require lots of tending to and care. They can offer up great blessings, similar to poppets, when well nurtured.

Many people use burdock in the home to ward against negativity; such as casting it as a powder, especially around the corners of the home. It can be added to any incense or blend for protection as well. Some traditions call for cutting the root into small pieces which can then be strung like beads on red thread to wear around the wrist or the neck for protection against ill intent and negativity.

Across cultures it seems burdock is a powerfully apotropaic amulet and symbol; no doubt its positive effects as a healing agent as well as its naturally occurring characteristics (the burrs) are what draws forward its properties as a defensive agent. Use in amulets, potions, baths, washes; or as part of a ritual meal.

Note:

This monograph is adapted from a series of courses taught in 2019 and 2020 and part of a larger project about the use of herbs and woods in a few select European smoke and water practices. I've focused on these practices as a way to point towards some traditions we all have access too, and in the interest of peeling back a few layers onto why these herbs are so popular in our contemporary traditions, today.

HERBAL RESOURCES

Alaric Albertsson, A Handbook of Saxon Sorcery & Magic: Wyrdworking, Rune Craft, Divination, & Wortcunning, Woodbury MN, Llewellyn Worldwide, 2017

Bingül Gündaş, What’s in a kilim? History and motifs, Istanbul The Guide, June 2020*

Brooke Bullock, Leechbook III, A New Digital Edition (A Senior Thesis)

— for mad-heart (with elecampane!)

— to aid digestion

— to aid in post-birth care

Burdock remedies in Duchas.ie

C. R. Bilardi, The Red Church Or the Art of Pennsylvania German Braucherei, Sunland CA, Pendraig Publishing, 2009

Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Medicinal Plants, An Ethnobotanical Dictionary, Portland Oregon, Timber Press, 2009

Deni Bown, Encyclopedia of Herbs & Their Uses, New York, Dorling Kindersley Publishing, 1995

E. Blackwell, 1737-39, A Curious Herbal

Erma Gunter, Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1945/1973

J.Cameron, Names of plants (Scottish and Irish) — web archive of Irish and Scottish names, associations, and sometimes folklore

John Michael Greer, Encyclopedia of Natural Magic, Woodbury MN, Llewellyn Worldwide, 2000

Oswald T. Cockayne; Leechdoms, Wortcunning, And Starcraft Of Early England, (an early translation of the Leechbook III and Bald's Leechbook) London : Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green 1864

Margaret Grieve, (1931). A Modern Herbal

M.Nurdan Taşkiran, Reading Motifs On Kilims : A Semiotic Approach To Symbolic Meaning, Academia.edu

Psychetolia, Well-Known Kilim Motifs & Their Meanings II

Stephany Riley, The History of Burdock, Naturally Simple

Duchas.ie is a resource acquired through Lora O'Brien, Irish Pagan School

*this came out a few months after our class, however I've included it here in the resources for further info!

CULINARY RESOURCES

Melitta Weiss Adamnson, Food in Medieval Times, Westport, Greenwood Press, 2004

Francoise Sabban, Odile Redon, Silvano Serventi; The Medieval Kitchen- Recipes from France and Italy, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1998

John Murrell: A new booke of Cookerie; London Cookerie, London 1615

Khristian S. Smith, Possets, drugs, and milky effects: A look at recipes, Shakespeare’s plays, and other historical references, Folger Shakespeare Library

Medieval Cookery, excerpt from The Prince of Transylvania's Court Cookbook (Hungary, 16th c.)

Alaric Albertsson, A Handbook of Saxon Sorcery & Magic: Wyrdworking, Rune Craft, Divination, & Wortcunning, Woodbury MN, Llewellyn Worldwide, 2017

Bingül Gündaş, What’s in a kilim? History and motifs, Istanbul The Guide, June 2020*

Brooke Bullock, Leechbook III, A New Digital Edition (A Senior Thesis)

— for mad-heart (with elecampane!)

— to aid digestion

— to aid in post-birth care

Burdock remedies in Duchas.ie

C. R. Bilardi, The Red Church Or the Art of Pennsylvania German Braucherei, Sunland CA, Pendraig Publishing, 2009

Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Medicinal Plants, An Ethnobotanical Dictionary, Portland Oregon, Timber Press, 2009

Deni Bown, Encyclopedia of Herbs & Their Uses, New York, Dorling Kindersley Publishing, 1995

E. Blackwell, 1737-39, A Curious Herbal

Erma Gunter, Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1945/1973

J.Cameron, Names of plants (Scottish and Irish) — web archive of Irish and Scottish names, associations, and sometimes folklore

John Michael Greer, Encyclopedia of Natural Magic, Woodbury MN, Llewellyn Worldwide, 2000

Oswald T. Cockayne; Leechdoms, Wortcunning, And Starcraft Of Early England, (an early translation of the Leechbook III and Bald's Leechbook) London : Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green 1864

Margaret Grieve, (1931). A Modern Herbal

M.Nurdan Taşkiran, Reading Motifs On Kilims : A Semiotic Approach To Symbolic Meaning, Academia.edu

Psychetolia, Well-Known Kilim Motifs & Their Meanings II

Stephany Riley, The History of Burdock, Naturally Simple

Duchas.ie is a resource acquired through Lora O'Brien, Irish Pagan School

*this came out a few months after our class, however I've included it here in the resources for further info!

CULINARY RESOURCES

Melitta Weiss Adamnson, Food in Medieval Times, Westport, Greenwood Press, 2004

Francoise Sabban, Odile Redon, Silvano Serventi; The Medieval Kitchen- Recipes from France and Italy, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1998

John Murrell: A new booke of Cookerie; London Cookerie, London 1615

Khristian S. Smith, Possets, drugs, and milky effects: A look at recipes, Shakespeare’s plays, and other historical references, Folger Shakespeare Library

Medieval Cookery, excerpt from The Prince of Transylvania's Court Cookbook (Hungary, 16th c.)